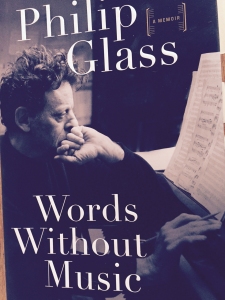

I recently read Words Without Music, a memoir by Philip Glass. Although I really know nothing about music—how people compose it, how they manage to play it, very mysterious—Glass’s thoughts about his development is a great read. It is not a conventional autobiography, but connected reminiscences about how he proceeded in life.

Glass is no universal example for how to build a career in the arts, but then nobody is. Nowadays you can’t proceed in the ways that Glass did in the 1950s, 60s and 70s. But, his attitude about how to become a professional can be very useful.

It helped that Glass’s father owned a record store and listened to classical music in the evenings at home. It was important that a 15 year old kid could get into the University of Chicago through an entrance exam without having to finish high school. It was a time when a young man going to Julliard, living in Paris, or making his way in the New York art/performance world could make a kind of living on part-time work, leaving time and energy for writing and performing music.

There are two main things that I learned about Glass through this book: he is a student and he is musically omnivorous.

In the 60s he traveled overland from Paris to India. His “significant purchase” before leaving Europe: a transistor radio—so he could listen to the music of Turkey, Iran, Afghanistan, Pakistan and India as he traveled though those countries—a tool for the omnivorous student. At the end of his journey he was in Kalimpong, once the Indian gateway to Tibet. There he met Tomo Geshe Rimpoche, a Tibetan monk, who at one point asked him, “What would you like to do?” Glass replied, ” I’d like to learn from you what you are willing to teach me.” Glass’s willingness to be open to being the student, throughout his life, is strangely impressive to me, because I have always been resistant to learning from a teacher (beyond the conventional classroom experience).

He studied composition with the famously demanding Nadia Boulanger in Paris for two years (when he was 27-29 years old). He needed to understand how to write music for strings, so he took violin lessons. He studied Indian music with Ravi Shankar. He studied tabla with Alla Rakha. He studied yoga. He studied qigong. Richard Serra offered him drawing lessons, but he never got around to that.

One other thing about Glass is his perseverance, but that seems, for him, innate. His first concert was in 1968, when he was 31. There were six people in the audience—and one of those was his mother. Eight years later Einstein on the Beach was sold out at the Metropolitan Opera. He would still be driving a cab for two more years, until, at 41, he could make a living through his music.

There’s a lot in this book, but I was left wishing there was more.

I recommend that you watch this documentary before you read the book. It might help you hear Glass’s voice in the writing:

Glass – A Portrait of Philip In Twelve Parts

A little reminiscence: Must have been 1972. I was in the White Gallery at Portland State University one evening, helping to install a show. Mel Katz stopped by. He had just heard some music performance at PSU, said it was really good, we should have been there. Really loud. Philip Glass. That was Glass’s first tour in the US. I missed that one.