I see that Jeff Jahn has repeated his thought that the new bridge be named for Mark Rothko. On PORT he says:

I’ve updated the both very popular and controversial post on the Rothko bridge naming. I see it as cutting a provincial gordian knot… so many (especially those who have been in Portland a long time) put a lot of effort into denying that the city’s most famous and accomplished resident ever lived here or had any real connection. The sentiment doesn’t hold up to the facts and illustrates why Portland has a hard time acknowledging highly ambitious people (provincialism). It is a good thing to get over.

That has led me to think further about this idea.

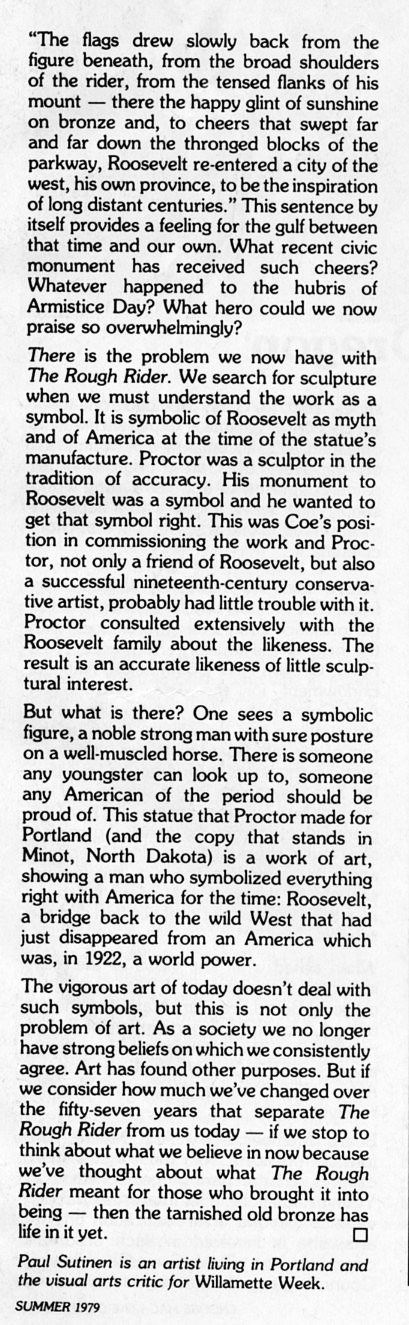

I don’t know who those “many” are who would be silly enough to deny “that the city’s most famous and accomplished resident ever lived here or had any real connection.” Why would anyone deny that Rothko lived in Portland from 1913-1921, from ages 10-18 and that he went to Shattuck School, now Shattuck Hall at Portland State University, and Lincoln High School, now Lincoln Hall at PSU? The evidence is clear in James E. Breslin’s authoritative Mark Rothko: a biography (“an excellent resource,” as Arcy Douglas said on PORT , June 17, 2009). Who could argue with that?

Perhaps it could be claimed that it was Portland, the city and its resources that gave the foundation for Rothko’s life after he left , but I have seen no compelling evidence of that (Later in life Rothko claimed that had he “remained in Portland, he would have been a bum,” [Breslin]). Perhaps Dvinsk, Russia should name a bridge for Rothko. As Breslin says:

Rothko’s desire to create artistic works that would provide a place for him, his difficulty in accommodating these creations to the real world of restaurants, museums and viewers, his combativeness, his prophetic ambitions, his intense desire for success, his guilt about success, his uncompromisingness, his compromises, his propensity to isolate himself, his wish for community, his mixed feelings about both wealth and poverty, his suspicions, his suspicions about himself, his vulnerability to despair—all these conflicting feelings in the Mark Rothko of the early 1960s had their origins in the life of Marcus Rothkowitz, born in Dvinsk, Russia, a despised Jew in the infamous Settlement of Pale, in the first years of the twentieth century.

If we look for the Mark Rothko who said, “I’m interested only in expressing basic human emotions—tragedy, ecstasy, doom and so on—and the fact that a lot of people break down and cry when confronted with my pictures show that I communicate those basic human emotions. … The people who weep before my pictures are having the same religious experience I had when I painted them” —those years in Dvinsk could easily be seen to be the root. Again, as Breslin says:

When Rothko himself recalled the first ten years of his life, he was most likely to remember Russian persecution. He was “very strongly interested” in “his Russian background,” according to his friend Herbert Ferber, and often repeated stories of his childhood—”being carried in the arms of his mother or a nurse at one time when a Cossack rode by and slashed them with a whip. And he had a scar on his nose which he claimed had been caused by the whip of a Cossack.”

I have yet find where anyone who knew Rothko said that Rothko was very strongly interested in his Portland background.

We could wish that something “Portland” influenced Rothko, but there is no significant evidence that Rothko found anything here that he would not have found during his elementary and high school years in a supportive Jewish community in any other city.

Of course it has been pointed out that Rothko came back to Portland several times (1933, 1944, 1949, 1967). He came to Portland to visit family. There is no evidence that the city itself had anything more for him.

And, there might be speculation about the landscape, but speculation is not clear evidence.

Jahn says that “Portland has a hard time acknowledging highly ambitious people.” I don’t quite understand what Jahn means by acknowledging in this regard. For me this whole thing still smacks of “grabbing at the coattails of someone who became a great artist.” Our ancestors (he left 92 years ago) had damn little to do with the success of Mark Rothko. This bridge naming thing remains something like getting one’s picture taken with a celebrity so you can claim a connection.

A MODEST PROPOSAL

Beyond the question of how Rothko related to Portland there is another important question:

How did Portland relate to Rothko?

Looks like the answer is: With indifference.

Yes, Rothko showed some of his work, along with some works by his students, at the Portland Art Museum in 1933. But now, 80 years later, the Portland Art Museum has yet to acquire a significant work by the artist. The collection, according to the online search tool, contains two modest works on paper by Rothko.

Over the past 80 years, Portland has not acknowledged Mark Rothko by doing the one “art” thing that artists will recognize: buying the artwork.

So, here’s my modest proposal: I will support the naming of the “Rothko Bridge” when there is an acquisition by the Portland Art Museum (or any other public entity) of a major work by the artist.

Otherwise we would be doing the one easy thing that costs nothing and we do not deserve a Rothko Bridge.

From what I’ve read of Rothko, I think he would agree: Money talks, bullshit walks.